Teachers and writers have a lot in common, as I pointed out in this article from 2008 -- most of which is still relevant!

Read MoreEveryone’s an educational expert, but it was ever thus

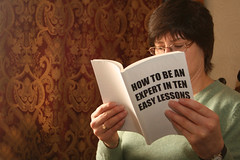

Have you noticed how everybody seems to be an expert on education these days? In fact, you only have to pick up a newspaper more or less any day of the week to find some minor celebrity saying something asinine like “Schools should teach kids how to stay safe online” (Really? What a great idea. How come we didn’t think of that?!). I don’t take much notice of these people, but it does annoy me when they somehow get on to conference programmes.

Have you noticed how everybody seems to be an expert on education these days? In fact, you only have to pick up a newspaper more or less any day of the week to find some minor celebrity saying something asinine like “Schools should teach kids how to stay safe online” (Really? What a great idea. How come we didn’t think of that?!). I don’t take much notice of these people, but it does annoy me when they somehow get on to conference programmes.5 ways to establish credibility on your blog

I don’t know what it’s like living in other countries, but here in England we are fortunate indeed. If I want to have a discussion on any subject at all, I can simply walk into the pub nearest to where I happen to be at the time, where I am virtually certain to discover a self-styled “expert” declaiming about the economy, or what’s wrong with kids today, or how to solve the financial crisis, or whether or not kids should be taught how to programme, or how the entire education system should be put right.

I don’t know what it’s like living in other countries, but here in England we are fortunate indeed. If I want to have a discussion on any subject at all, I can simply walk into the pub nearest to where I happen to be at the time, where I am virtually certain to discover a self-styled “expert” declaiming about the economy, or what’s wrong with kids today, or how to solve the financial crisis, or whether or not kids should be taught how to programme, or how the entire education system should be put right.

The expert ICT teacher and Something Borrowed

What can we learn from a band about the characteristics of the expert ICT teacher?

What can we learn from a band about the characteristics of the expert ICT teacher?

Three downsides of the idea of the guide on the side

Teachers and writers

Teachers and writers perhaps have more in common than people realise. Yesterday I visited the London Book Fair, and that helped me to gather my thoughts on this matter....

- The most important element in the education system is, in my opinion, the expert teacher. You can verify this by the economist's approach of determining the marginal cost of something by taking it out of the picture completely. If you take the expert teacher out of the classroom, and replace him or her with non-expert teachers following, to all intents and purposes, a script, then I think you would very quickly see that to have been quite a costly move, whether in terms of behaviour or examination results or enthusiasm for the subject on the part of the students or whatever.

Note that I am not necessarily restricting myself to subject expertise. A good teacher can take a subject they know very little about and, with the help of good materials and training, do a reasonable job of teaching. The important element here is pedagogical expertise. Of course, if the teacher is an expert in both pedagogy and the subject, so much the better.

On the other hand, if advisers, consultants and speakers were to disappear from the educational scene, would that make a huge amount of difference? Let me rephrase that. It would make a great deal of difference, of course, but would it make a very big marginal difference? Let's put it another way: if you wanted to increase educational standards in your area, and you had to get rid of either an expert teacher or a consultant, adviser or visiting speaker, in order to balance the books, whom would you choose to get the chop?

Please bear in mind that I am trying to be objective here. I am myself a consultant and visiting speaker, and have been an adviser; and some of my best friends are speakers, advisers or consultants.

The most important element in the publishing industry is, in my opinion, the author. Publishers will argue otherwise, of course, because many books these days are not so much written as produced. The Dorling Kindersley books are an excellent example of this: lavishly illustrated, beautiful to look at, but not necessarily easy to read because of all the colours and pictures, though that's another matter and a personal opinion anyway.

But again, look at this at the margin. Other things being equal, if you had to cut costs by getting rid of an editor, an illustrator or an expert writer, surely your decision would not be to fire the writer? - The curious thing, though, is that when it comes to trade shows, both the teacher and the writer share the ignominy of being regarded as unworthy of much attention, generally speaking. Visit the BETT show, say, with the word "teacher" on your badge, and you will not be treated as well as if you have, say, "Chief Software Buyer" displayed. The reason is obvious, of course.

The same obtains at shows like the London Book Fair. The "most important" people there are the ones who buy and sell rights. Authors? Don't make me laugh. As soon as exhibitors see "Author" on your badge, they either humour you as politely and briefly as possible, or else ignore you all together.

This is so pronounced that after it had happened to me the first time, I thought I must have developed some sort of personality defect or acute paranoia. But then the following year I tried an experiment: I asked my wife to accompany me, and she discovered exactly the same thing. Then the following year I spoke to someone who works for the UK's Society of Authors, and she said it was a common experience: authors are regarded with disdain.

This year I tried another experiment. Instead of "author", I described myself as a "Digital Content Provider". This was definitely a good move: I had much better conversations with people. Even so, I made a special effort to visit one particular exhibitor, but when I arrived one of the people manning the stand peered at my badge and then, clearly deciding that I was of no use to him at all, did not simply ignore me but completely turned his back to me. The man is an idiot: thousands of people read my articles, and that company is definitely one that they will never hear about from me. - People's attitude to both teachers and writers is ambivalent. When I was a teacher, people used to say "I don't know how you can do that job, the way kids are today". And a moment later those same people would tell me what an easy life I had, with those short days and long holidays.

At the same time, everyone thinks they can do it. A doctor we met a few weeks ago said that teaching is easy because all you have to do is and at the front of the class and tell the kids what you know. That's the thing about experts: they are so adept at what they do that they make it look easy. A bit like doctors you might say.

So it makes you wonder why there is a teacher recruitment crisis in the UK, the job being so easy and all. A recent study shows the state of teacher recruitment in the UK to be less than optimal, whilst an article in the Times today claims that there has been a massive increase in the number of unqualified teachers practising in UK schools, with two thirds of them coming from overseas. The study referred to earlier also suggests that in information and communications technology, the number of places on post-graduate training courses will not be filled this year.

But you get the same thing in the field of writing. There are tons of books on the market about how to write a best-selling novel, which suggests that it must be hard to do, yet half the population is attempting to write a best-selling novel. That's anecdotal, by the way, and no doubt a huge exaggeration, but there does seem to be a large number of people who are writing a book at any given time, so they must think it's easy. In fact, you just have to look at the number of blogs that get started and go nowhere (the number is always changing, so I haven't given one, but it's a lot) to see that it's the case that lots of people think writing must be easy.

But both good writing and good teaching are not easy for most people, they only look "easy". I would suggest that part of the reason is that both good writing and good teaching actually take a lot of effort. Even the teacher that says he just plans his lesson on his way to the lesson has brought to bear a vast repository of knowledge and experience, and the same goes for most writers. What's the expression? 10% inspiration and 90% perspiration? I think that applies in both cases. - Both teachers and writers can be precious. The second hardest thing in the world is giving negative feedback to a teacher whose lesson you have just observed. The hardest thing in the world is suggesting to a writer that she changes a few things.

That's why, to take the first example, I am always careful to give positive feedback followed by some suggestions. There's not usually much point in doing it another way, because the person you're talking to simply shuts down and doesn't hear anything positive or useful.

And to take the second example, I know that when I receive suggestions on my book chapters from an editor, I have to make a conscious effort to read the suggestions objectively, rather than as implied criticisms. But it's really hard to do. - In both writing and teaching, training and experience are all-important. Yes, there are "natural" teachers, just as there are "natural" writers, but raw talent is not usually enough. I think no matter how good you are, you can always hone your craft. Indeed, one of the most common traits of experts is that by and large they think they don't really know anything, at least compared to the vast amount that they do not know.

- Neither teachers nor writers work well with templates. I have recently been asked to write some book chapters in a template, and found it stifled rather than released my creativity. In the end I wrote the chapters and then, just to keep the peace, reverse-engineered them so that they fitted the template. I don't think the publisher noticed.

- Finally, for all the reasons described, and probably more, I don't think either teachers or writers could be replaced by machines, except in very specific circumstances and under highly-specified conditions. I find it interesting that science fiction writers of old routinely predicted the use of teaching machines or robot teachers, but almost universally failed to predict the decline in smoking. It's because they focused on the technology rather than behaviour, in my opinion.

However, I have to say that I loved the idea propounded in one episode of The Avengers, in which a publishing company churns out novels by getting an elderly woman to play the piano. Soft, mellow sections create "gooey" passages in the book, and so on and so on. When the music playing is over, a manuscript pops out of the side. Delicious!

This article was first published on 16th April 2008.

Oh, Sir, You are too kind

Reading through people's blogs, especially those of educators, one thing that strikes me is what a nice bunch we are. Even David Warlick's rant is, essentially, nice. Jeff Utecht's recent blog about fear is, essentially, kind. Everything they say and everything others say about barriers to implementing the use of educational technology across the school is correct, but I also believe that part of the problem is our willingness to make allowances.

It is usually at this point that people who know me call me a grumpy old man, but in my mind I am an angry young man! Surely there are some things which we must regard as simply unacceptable? Period?

Here is a personal example of what I find unacceptable. One of my relatives asked me last Sunday if I could create a Word document for her so that she could type a list of dates. She has been teaching, I believe, for over 20 years, and is in a senior position in her school. Why has she been allowed to get away with such a basic lack of knowledge for so long?

In this particular instance it doesn't have any direct effect on the children she teaches, or the staff she manages. Or does it? I am a firm believer in what has been called the "hidden curriculum", in which what you teach and what the kids learn may be rather different. What are her children and staff learning from her behaviour? I would say the following:

1. Technology is relatively unimportant, otherwise she would have learnt how to use it to some extent (I even had to show her how to get from column one in the table to column two, and how to save her work).

2. That it's OK to let people know that your are technologically illiterate.

3. That, from the point of view of one's employer, it is OK to be technologically illiterate.

4. That if you appear helpless enough someone will help you.

I think that although that list is based on just one personal incident, we can extrapolate from it and reasonably conclude that it probably applies more generally. So here is my "wish" list for education, which I think we should adopt as a baseline set of standards.

Before I give my list, I should like to say this. The first step in establishing a standard is to state what that standard is, and/or what it is not. Just because you may not know how to go about achieving it is certainly no reason not to state it. For example, in my classes I always had expectations in terms of acceptable behaviour. It would sometimes take me three months to achieve them, desoite teaching them every single day, but that's besides the point.

Here is my list:

1. All educators must achieve a basic level of technological capability.

2. People who do not meet the criterion of #1 should be embarrassed, not proud, to say so in public.

3. We should finally drop the myth of digital natives and digital immigrants. As I said in my blog, in the context of issuing guidance to parents about e-safety:

"I'm sorry, but I don't go for all this digital natives and immigrants stuff when it comes to this: I don't know anything about the internal combustion engine, but I know it's pretty dangerous to wander about on the road, so I've learnt to handle myself safely when I need to get from one side of the road to the other."

The phrase may have been useful to start with, but it's been over-used for a long time now. In any case, after immigrants have been in a country for a while, they become natives. We've had personal computers for 30 years, and I was using computers in my teaching back in 1975. How long does it take for someone to wake up to the fact that technology is part of life, not an add-on?

4. Headteachers and Principals who have staff who are technologically-illiterate should be held to account.

5. School inspectors who are technologically illiterate should be encouraged to find alternative employment.

6. Schools, Universities and Teacher training courses who turn out students who are technologically illiterate should have their right to a licence and/or funding questioned.

7. We should stop being so nice. After all, we've got our qualifications and jobs, and we don't have the moral right to sit placidly on the sidelines whilst some educators are potentially jeopardising the chances of our youngsters.