These days, doing a good job as an ICT or Technology Co- ordinator/Subject Leader is not enough. In order to get on in your career, you have to be seen to be doing a good job.

In this new series, Alison Skymes looks at ways of making a good impression. Today: generating a buzz.

Alison SkymesBefore I look at this, I just gotta tell you something that neatly follows on from what I was going on about last time. I ended my piece by saying you should use a spell-checker. Well, it's a pity that an IT consultancy company I came across didn't take my advice. Their "representative" (actually, some 20- something studenty-type) thrust a flier into my hand.

Alison SkymesBefore I look at this, I just gotta tell you something that neatly follows on from what I was going on about last time. I ended my piece by saying you should use a spell-checker. Well, it's a pity that an IT consultancy company I came across didn't take my advice. Their "representative" (actually, some 20- something studenty-type) thrust a flier into my hand.

I read it because I had nothing better to do at that particular moment. So here's what greeted me:

"Benefit from Consultancy from the proffesionals."

Why does "Consultancy" start with a capital "C"? Why is "professionals" spelled incorrectly? Why is the word "from" used twice in the same sentence?

Those aren't the only errors, of spelling, grammar and sentence construction. Now, maybe I am looking at this the wrong way, but if these people can't even be bothered to take care over their own flier, can I really trust them to look after my IT systems? Doesn't exactly inspire you with confidence, does it?

OK, on to today's topic: creating a buzz. Here are 7 points you need to know:

1. Question: what's creating a buzz got to do with creating a good impression? Answer: plenty. Looking at it from your boss's point of view, she has spent gazillions on educational technology: the least you can do is get people excited about using it. Because, at the end of the day, that's the only thing that really counts anyway. If the technology is being used, and people are excited about using it, that will create a warm glow in the hearts of the powers that be. And that can only be a good thing, especially when it comes to dishing out the money.

2. In case you're still not convinced, take a leaf out of the politicians' book (yeah, yeah, I know). Basically, if you can't or won't actually do anything, then at least shout about it. Of course, this approach is fine for politicians for whom the long run doesn't exist. Ideally, you should have something behind the "spin". But my point is this: Woody Allen said that 80% of success is showing up. I say that 90% of the remaining 20% (is your head hurting yet?) is telling people about it, whatever "it" happens to be.

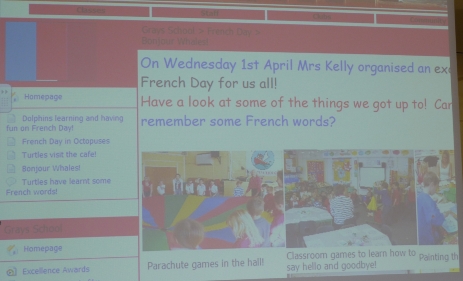

3. Make your space welcoming. Most computer labs look like something out of Stalag 17: full of notices telling you what you cannot do. How about some positive posters telling you what you can do -- and how to do it? Hey, and don't forget to include lots of examples of children's work: posters from the journals may be colourful, but they don't generate buy-in from the kids or their parents, and so they don't generate buzz.

4. Not if but when. If you say to a student "If you go on to take this subject at a higher level...", or "If you do well in this subject...", you're suggesting there's a possibility that the opposite will be the case. Be positive. Set your expectations high. People have a tendency to live up to, or down to, the teacher's expectations. Nobody ever created a buzz by making everyone else feel depressed.

5. Do some exciting work. It is possible to think outside the box and still meet all the National Curriculum requirements, or the equivalent standards in your country. Don't bore the pants off the kids: what have they ever done to you?

6. Put on exciting events. At open days or parents' evenings, have an automated rolling display, like a SlideShare or PowerPoint slide show, or a video containing interviews with the students saying how great the course is. Probably best not to bribe or threaten them though.

7. Above all, enjoy yourself. Enthusiasm begets enthusiasm. Be upbeat about what you do, and what the kids and your team are doing.

Tomorrow: If brevity be the soul of wit...