I attended a fascinating talk at the RSA last September. In a lecture entitled “The Internet: Empowering or Censoring Citizens”, Evgeny Morozov questioned whether the internet really is the means to inevitable freedom and democracy it is often portrayed to be.

‘So what?’, you may ask. From an educational point of view I think this is an important topic for discussion for two reasons. The first is that, in general terms, we should take every opportunity to ‘force’ students to think for themselves. When I was a teacher, I usually adopted Oscar Wilde’s stance:

“Don't say you agree with me. When people agree with me. I always feel that I must be wrong.”

Students need to be encouraged to seek questions, even if the answers are not as readily forthcoming.

Matthew Taylor and Evgeny Morozov at the RSA

Matthew Taylor and Evgeny Morozov at the RSA

Secondly, in every ICT course, apart from purely skills ones, there is a section on the effects of technology on society. By examining issues such as whether or not the internet is automatically a means of distributing power more evenly in a society, the teacher would be addressing the spirit (if not always the letter) of that section.

Morozov challenged the view of the people he refers to as ‘cyberutopians’ that connectivity + devices = democracy. Some states, he pointed out, are using the web to crack down on dissidents.

In his talk, the link to which is given below, he described a number of ways in which some countries are using the power of the web to curtail, rather than to extend, democracy and freedom. If you think about it, it is obvious that web 2.0 applications are not inherently good or bad, so why would it be so surprising to discover that countries use them for their own ends?

In this context Morozov spoke of the ‘spinternet’. The idea is that when deletion of content is, in effect, impossible, the next best approach to dealing with what we might call off-message sentiments is to use political spin to defuse the issue.

The general and simplistic view seems to be that once every young person in a country has an ipod, they will miraculously turn into democrats. This ipod liberalism, as Morozov terms it, represents a deterministic view. It seems to me to be pretty insulting too. After all, if someone gave you an ipod, would your principles and beliefs suddenly fly out of the window? I realise that that is a somewhat simplistic counter-argument, but no more so than, it seems to me, the argument itself.

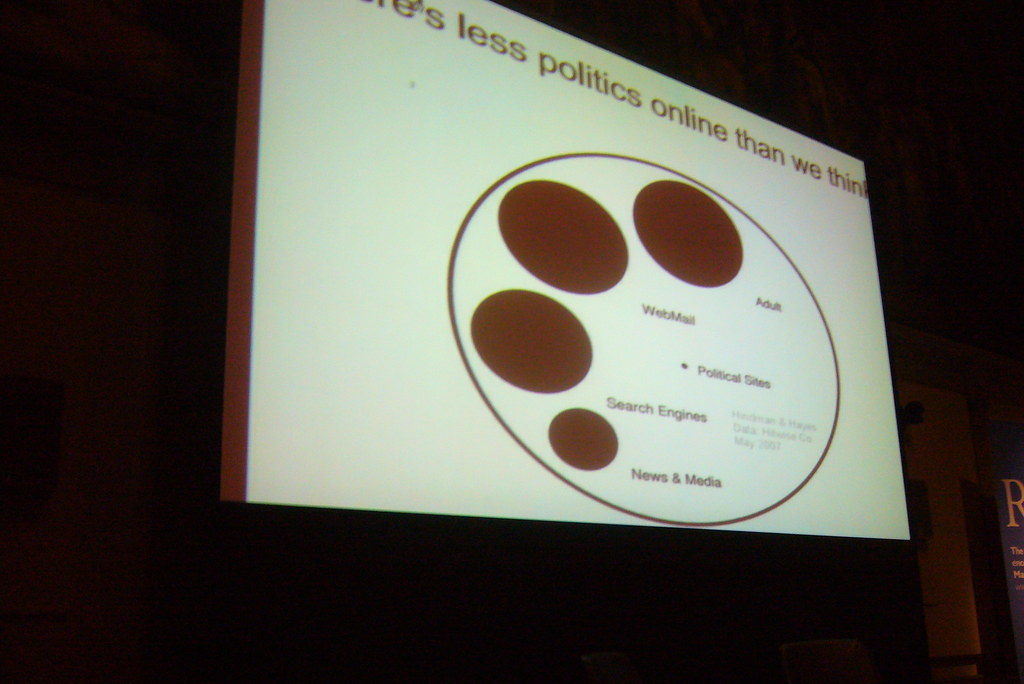

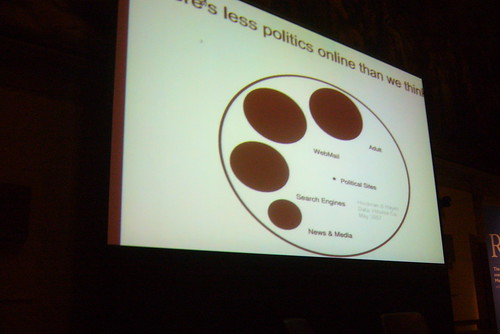

In any case, a more realistic approach would be to recognise the existence of cyberhedonism: most people are not interested in politics, as shown in this illustration:

Online politics

Online politics

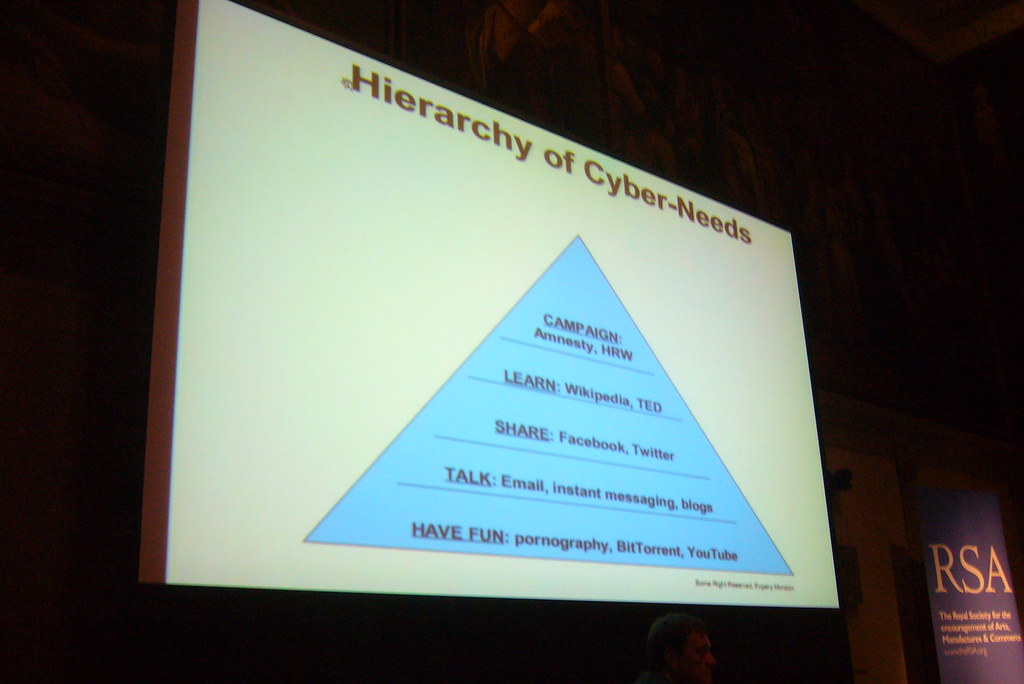

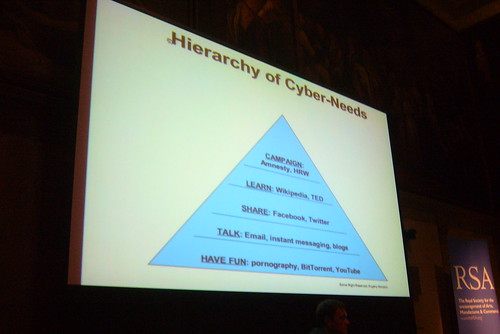

And perhaps we need to borrow from Maslow and draw up a hierarchy of cyberneeds (see illustration below). In this paradigm, internet users start by satisfying their basic ‘needs’ – for pornography, file-sharing and video downloading – before progressing to less self-centred activities.

Hierarchy of internet needsTowards the end of his talk, in an almost throwaway comment, Morozov vividly illustrated the power of the web in the ‘wrong’ hands. In the past, he said, a totalitarian regime would have to torture an activist to find out the names of his associates. Now all they have to do is go on Facebook.

Hierarchy of internet needsTowards the end of his talk, in an almost throwaway comment, Morozov vividly illustrated the power of the web in the ‘wrong’ hands. In the past, he said, a totalitarian regime would have to torture an activist to find out the names of his associates. Now all they have to do is go on Facebook.

Of course, it’s easy to point the finger at totalitarian regimes, but even in countries like the UK and USA, power is not evenly distributed on the web. For example, half of Wikipedia’s articles are accounted for by only 10% of its users (Clay Shirky has drawn attention to this sort of thing as well). There is nothing nefarious in this, of course, but it’s salutary to bear in mind that, according to Morozov, the average person stands only a 2% chance of being mentioned on the front page of Digg. Hardly an even distribution of influence.

It seems to me that a number of questions might fruitfully be discussed with students:

What do you think of Morozov's arguments?

Is the concept of a hierarchy of cyberneeds a useful one?

Does it exist?

Where would your students place themselves in that pyramid?

Where would you and your colleagues place yourselves?

If web 2.0 applications can be manipulated by governments and even individuals, how can one guard against being taken in?

Is being digitally literate enough?

One of the key points to come out of a discussion about these issues would surely be that of identity? Morozov focused mainly on the use of Web 2.0 applications by non-democratic governments, but the truth of the matter is that you actually don’t know who you’re ‘talking’ to in any online space unless you do a bit of research and cross-checking. How do you know that the word-of-mouth recommendation you have just received is genuine?

How do you know whether or not the person ‘bad-mouthing’ a particular product is working for a rival company?

How do you know if an Amazon book review is genuine?

And is it not crucial, therefore, that we take some issues out of the ‘niche’ area of e-safety and bring them into the mainstream, or widen the definition of e-safety to include such issues?

Further reading:

Read Matthew Taylor's blog post about this (which centres on the political rather than educational implications of Morozov's address) and, especially, the comments. I especially like Taylor's conclusion:

The web is changing culture, relationships and organisations. Its effects are real and important. Sometimes they are good and sometimes not. The exaggerated claims of those who say the internet is inherently a destroyer of organisations and hierarchies or that it is bound to lead to greater democracy and collaboration are an unhelpful distraction from the important study of the internet’s real impact on real lives.

The internet society – time to get real

Listen to Morozov's talk

This article was first published on 30th September 2009.