This was the title of a seminar which Miles Berry and I presented at the 2009 BETT show. The more I think about it, the more important it seems to me that teachers know about what their students can do.

Soon after the BETT show I had occasion to give a presentation in Rotterdam, on the subject of the potential of ICT in education. Again, I did some research and discovered, perhaps not surprisingly, that what young people do and can do in terms of technology is pretty much the same in The Netherlands as it is in the UK as it is in Europe as a whole as it is in the USA.

What do young people do online at home?

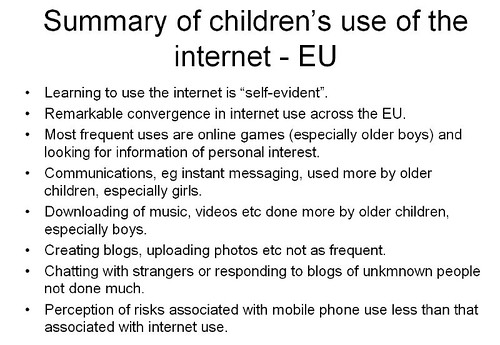

This is very much a broad-brush picture, but from the research and reading we have done, it would be true to say the following.

- It may be politically incorrect to say so, but boys and girls tend to conform to gender stereotypes online as well as offline. For example, boys prefer playing games to writing blogs.

- Youngsters really do multitask, because the percentage of their time spent on various activities adds up to a lot more than 100%.

- Despite the emphasis on creativity at the moment, youngsters aren't really all that creative, in the sense of creating stuff, compared to other things they do online.

Summary from http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/activities/sip/docs/eurobarometer/qualitative_study_2007/summary_report_en.pdf

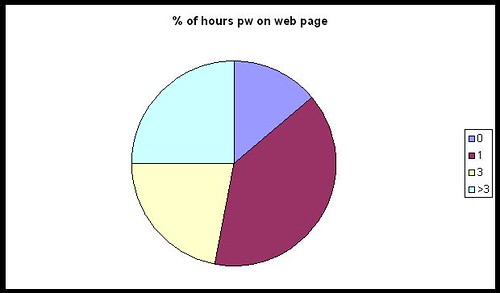

I find it interesting that youngsters are still mainly consumers of content than creators of content. Mind you, it depends on who you ask, of course. In Larry Rosen's Me, MySpace and I, nearly everyone surveyed spent a lot of time tweaking their web page. How surprising is that?

- From their responses, it would seem that young people use the web mainly for "sensible" things, like communicating with friends and doing homework.

Well the chatting to friends I can believe, but homework? I am not completely convinced by that, and I think what we may have here is evidence of some sort of experimenter effect. I wonder if the results would be different were the same surveys to be conducted by young people?

If it is true, I personally think that's something to be concerned about rather than something to celebrate. Kids should be enjoying themselves, not using every spare moment to better their grades.- The overall impression one gains from all the research is that technology is indeed very much a part of young people's lives. They spend an inordinate amount of time using it, and have a facility for grasping how to use it, at least in a superficial or immediate sort of way.

Whether they are able to easily delve deeper into an application or device, or use it in ways for which perhaps it may not have been intended, is an interesting question.

Like I said, a very broad picture. If you'd like more detail, take a look at the slides from our presentation at Miles' blog. We hope to have the audio accompaniment soon.

Why is this important?

I think we would all agree that it's good practice to base our teaching on what our students already know, understand and can do. If you don't, you run the risk of alienating through boredom and lack of challenge, or through setting work which they find impossible. (These were two of the ten causes of ICT lessons being boring that I identified in my seminal work, Go On, Bore 'Em: How to make ICT lessons excruciatingly dull.)

What this research shows, I think, is that you cannot simply go by what you know they can do from what they have done in school. You also need to find out what they do when they are not in school.

What can you do about it?

The obvious answer is: find out what they can do! You could set up a survey using Google Docs (Go to New-->Form). The results end up in a spreadsheet, making analysis relatively straightforward.

If you include questions like what primary school they went to, if you're in a secondary, that in itself may yield some interesting results. You will need to include age and gender, of course.

If you decide to ask students to give their names, you will need to respect their privacy and not pass that information on. That would be my position, anyway, but you may be in a different situation. In my opinion, it's probably a lot easier to either say that names are optional or simply not to include a field for it. Much more pertinent would be information like the class or registration or option group the students are in.

Feel free to "steal" the questionnaires used by Miles and myself: you'll find the links here.

None of this is intended to be a piece of academic research; rather, it is intended to give you a good basis for deciding on what to teach and where to pitch it.

At least one person left our seminar with the intention of running his own survey within his school, and both Miles and I have said we would be interested in the results of his findings. We'd be interested in yours too, if you decide to do something like this.

One last word, about presenting the results. Miles used Wordle to generate word clouds from the answers to some of the questions. The results, which are very interesting, are here.