Look, before you say anything, yes I know that we are in the middle of a pandemic, and yes I know that what we think we know is changing all the time — and no, I have never managed anything in a pandemic. But the Department for Education has form, as they say. It’s not like they have always been great communicators is it? Let’s look at examples.

Keeping up with DfE Updates, by Terry Freedman

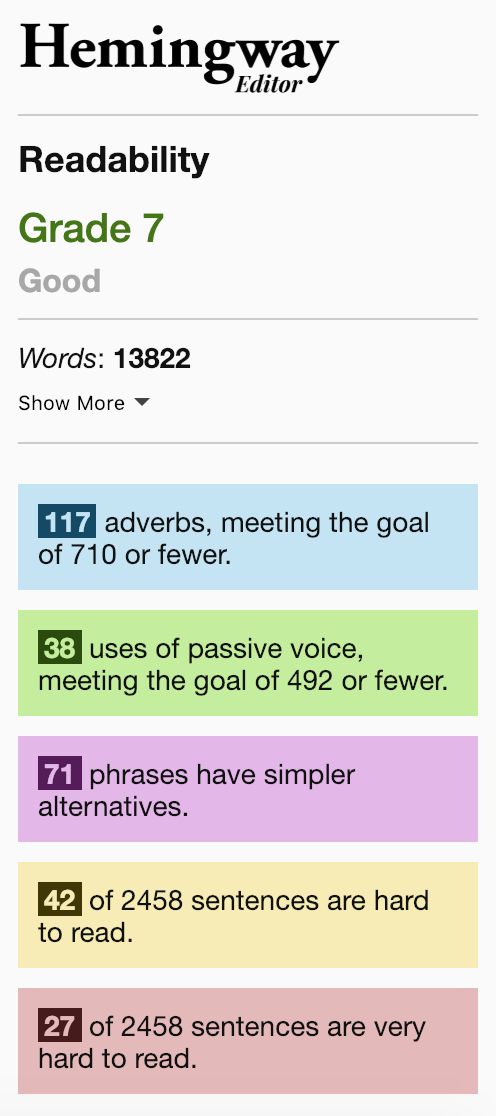

The education technology strategy

When they brought out the ed tech strategy, I did a textual analysis of it using Hemingway, and discovered that it's full of corporate claptrap, like driving the agenda forward, delivering ambitions etc. One person told me that he has become so used to this sort of thing he didn't even notice until I pointed it out. Here’s a screenshot of my analysis:

Hemingway analysis of the ed tech strategy, by Terry Freedman

My contention is that if you want to be taken seriously by teachers, at least sound like you know how to talk to them. As I said in the article I wrote about it, people in school really don’t talk like that:

“Morning, Fred. Ready to try and pummel some knowledge into our customers this sunny day?

Indeed, headmaster. I have adopted a user-centred approach in order to deliver my challenges in the classroom, and in so doing to drive forward the agenda.

Great! Fancy a cup of tea?”

Here's the article if you wish to read it:

Solution

Use the language and style of your target audience.

In future, have the document sent out to a team of beta readers, which is what (good) authors do. These beta readers should be drawn from the target audience, ie teachers and senior leaders.

Amend the document in the light of the comments and suggestions made by the beta readers.

Using beta readers is a reasonably certain way of avoiding this situation:

A document is written by people who think that “driving agendas” and “delivering aims” are (a) meaningful phrases and (b) used by real people who have better things to do than write this guff, and

The document is then read and approved by people who have had a similar “education” and think the same way, but happen to be more senior than the people in phase 1.

The guidance on schools reopening after lockdown

If you look at the DfE's guidance for schools reopening — on safety measures, and actions for schools —, it comes to 10,978 words, which would take approximately 43 minutes to read -- and that's without reading all the links within the two documents. All that, and no executive summary that says, in effect: Here are the 10 things you need to know/do by 15 June. (That was the target date for reopening schools, and the last time the guidance was updated was on 16 June, at the time of writing.)

I’m being slightly unfair. There is a list of key issues at the end of the latter document. This is over 2,200 words long even after taking out the bits that are irrelevant for schools.

I did a Hemingway analysis for these documents too. Here’s what it looks like for the two sets of guidance taken together:

Analysis of DFE back-to-school guidance, by Terry Freedman

Now, this bears some scrutiny. One of the aims of the English National Curriculum is to ensure that all pupils:

“write clearly, accurately and coherently, adapting their language and style in and for a range of contexts, purposes and audiences”

The DfE, far from leading by example, fails abysmally in this regard:

It’s not very readable — grade 14. This is an ok grade for adults, but when you consider that Heads have had to get to grips with a lot of complex information and challenges very quickly, it should have been made much simpler.

Over half of the sentences are hard or very hard, which explains the preceding point.

Solution

Take note of the Hemingway analysis: sentences could definitely be made less complex.

Include a “TL;DR” section at the beginning which gives the gist of what needs to happen, without all the detail.

Include also a list of action points, a checklist, so people can delegate tasks as needed and tick off items as they are completed.

Updates

The number of amendments and updates was astonishing. I stopped counting how many updates there were to these docs (I wish I hadn't now), but it's a classic sign of bad management, a sign that the people writing the stuff either (a) don't have a clue what they're doing, (b) don't have a strategy, (c) are backside-covering or (d) some combination of those three. I've written about my personal experience of this sort of management here:

https://www.ictineducation.org/home-page/bad-management

Now, I realise that the situation was (is) changing rapidly, and that perhaps the people concerned were trying to do the best they could in difficult circumstances. However, we’re used to this sort of thing: updates last thing on a Friday evening, or at the start of half-term or the Christmas holidays. There comes a point where people become fed up and cynical, so that when there is a series of updates, one after the other, for perfectly good reasons, it’s hard to give the DfE the benefit of the doubt.

OK, so the number and rapidity of updates to the guidance cannot be helped. But there are things the DfE could do to make the situation easier.

Solution

Take a leaf out of the software developers’ book. They number the versions, and when there is an update they publish what has changed. Writing that the guidance has been amended to take into account the fact that the government’s five tests have been met is completely unhelpful, because you still have to read through the whole thing to try and see what exactly has changed.

It would be even more helpful if the paragraphs were numbered too. Then the “What’s changed?” section at the start could say things like “Paragraph 14 no longer applies”, or “Paragraph 14 has been updated”.

Concluding remarks

The suggestions I’ve made are common sense. They take into account the fact that teachers and senior leaders are extremely busy, and don’t have time to spend nearly 45 minutes reading the same documents over and over again in order to play “Spot the difference”.

They would not be difficult to implement.

And they would portray the DfE at least making an effort to live up to the aim of the English National Curriculum cited earlier:

To ensure that all pupils:

write clearly, accurately and coherently, adapting their language and style in and for a range of contexts, purposes and audiences