In his article The Future of Assessment, Stephen Downes expresses his belief that the real future of assessment lies in systems that can “taught to analyse and assess responses to an open-ended question”.

Unfortunately, much as I’d like to be persuaded that this is indeed the case, I have serious misgivings.

The Black Box Problem

The first is that AI as it works at the moment is a black box. It reaches conclusions in a way that is hidden from view. In other words, we often don’t know how the program produced the result it did. Indeed, as Rose Luckin points out in her book, Machine Learning and Human Intelligence, the program itself doesn’t know how it reached the conclusion. It has no self-awareness or meta-cognition: it doesn’t actually know how it ‘thinks’.

This means that, from a philosophical point of view, we are prepared to take the word of a program that can process data much quicker than we ever could, but which has no idea what it’s doing. Unfortunately, even if you have little time or patience for philosophical considerations, there are practical pitfalls too.

Automation Bias

This is where people trust technology more than they trust a human being. I came across a good example of this a few years ago, when I was inspecting the computing department of a school. The assessment program they were using took the students’ answer to test questions, and then told the teacher what ‘level’ the students were on. There was no indication of how it worked them out.

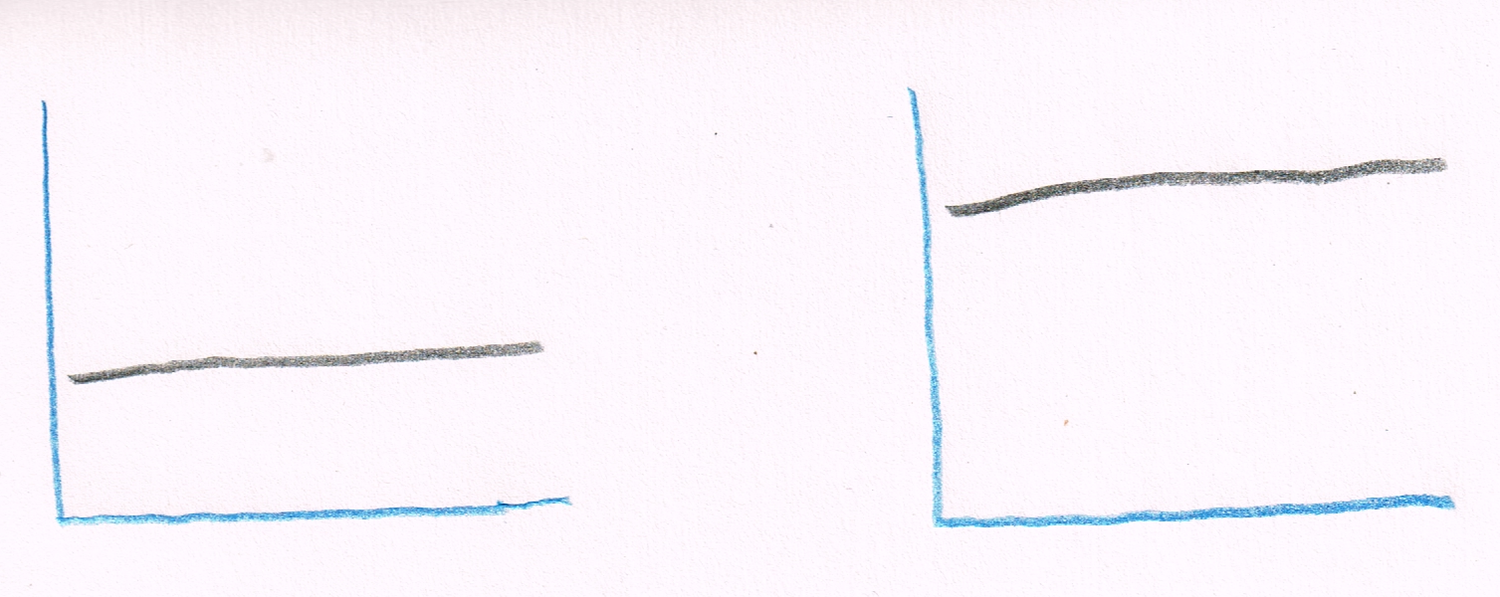

A teacher showed me two graphs of his students’ achievement, as measured at the start and the end of a term, using that program:

Before and after: “See, it’s gone up.” Picture credit: Assessment graphs, by Terry Freedman

“See?”, he said. “The numbers have gone up!”.

“Yes”, I said, “But what do the numbers actually mean?”

He looked incredulous that someone could actually ask such a stupid question. “Who cares? They’re higher, aren’t they?”

That’s a great example of automation bias. When it comes to AI, when the computer tells you an essay is worth a B+, you are inclined to believe it without question. After all, the AI has ‘learnt’ what a good essay looks like, so it must be right. This attitude will dramatically lower the usefulness of an AI system that marks essays. As unlikely as it sounds, one of your students could come up with a completely new theory about, say, Economics. (It has been known: when J.M.Keynes was asked why he had failed his Economics examination at Cambridge, he replied that it was because he knew more about Economics than his professors.) Since the AI has learnt what the ‘correct’ answer is, it will mark the student’s essay as wrong. Imagine what would have happened (or not happened) had Newton, Copernicus or Darwin been assessed by an automated essay marker.

What Are The Students’ Misconceptions?

A related danger is that, if the AI is correctly marking the essay without any input from a teacher, the latter has no opportunity to see what misconceptions the student has developed. If you believe, as I do, that the purpose of education is learning stuff, then this process entirely misses the point. Of course, if the purpose of ‘education’ is to give students’ work grades, I suppose it’s fine. (In which case, I think you’ll enjoy, and find useful, 6 Ways To Respond To Requests For Pointless Data.)

I enjoyed reading a book called Why They Can’t Write, by John Warner. In it he poses a question that goes right to the heart of matter:

If an essay is written and no one is there to read it can it be considered an act of communication?

I think most people would have to answer “No”, which kind of renders the whole exercise pointless.

Incidentally, you might like to read this brilliant review of my new book. The review was written by AI, and the book doesn’t actually exist.

You might also be interested in my review of Story Machines, which examines AI used to write fiction.