When it comes to teaching any subject, "hands on" is definitely a great way of engaging kids. This especially applies to teaching computing, obviously. But I am talking about making the past come alive.

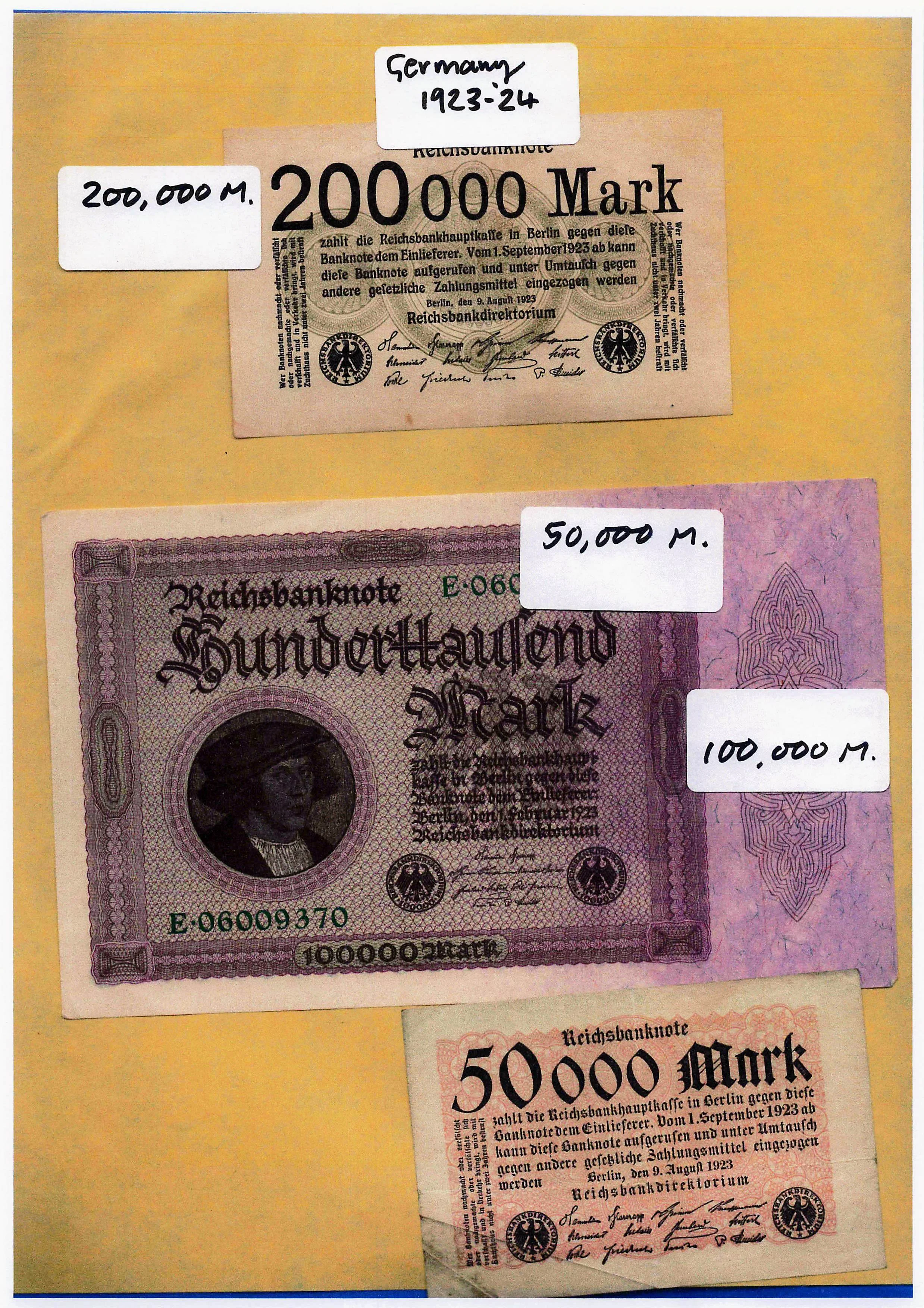

When I was teaching Economics, one day in a local market I happened to come across a stall selling bank notes from the German hyperinflation era -- you know, when a wheelbarrow full of money was less valuable than the wheelbarrow itself. These were goung for a song, and so I bought them, put them in one of those display books that artists and other creatives use to present their ideas to potential clients, and then took that into school.

I taught a lesson about inflation while the students took turns to look at these bank notes of impossible denominations -- notes that had been used by real people. The students were fascinated.

Original bank notes. Photo by Terry Freedman

Original bank notes. Photo by Terry Freedman

Original bank notes. Photo by Terry Freedman

Difference Engine Number 2

After I'd switched to teaching Computing, I had a similar experience when I printed off a picture of Eniac and showed the kids what computers used to look like. Far from being something you could have on your desk, they were things you could walk around in!

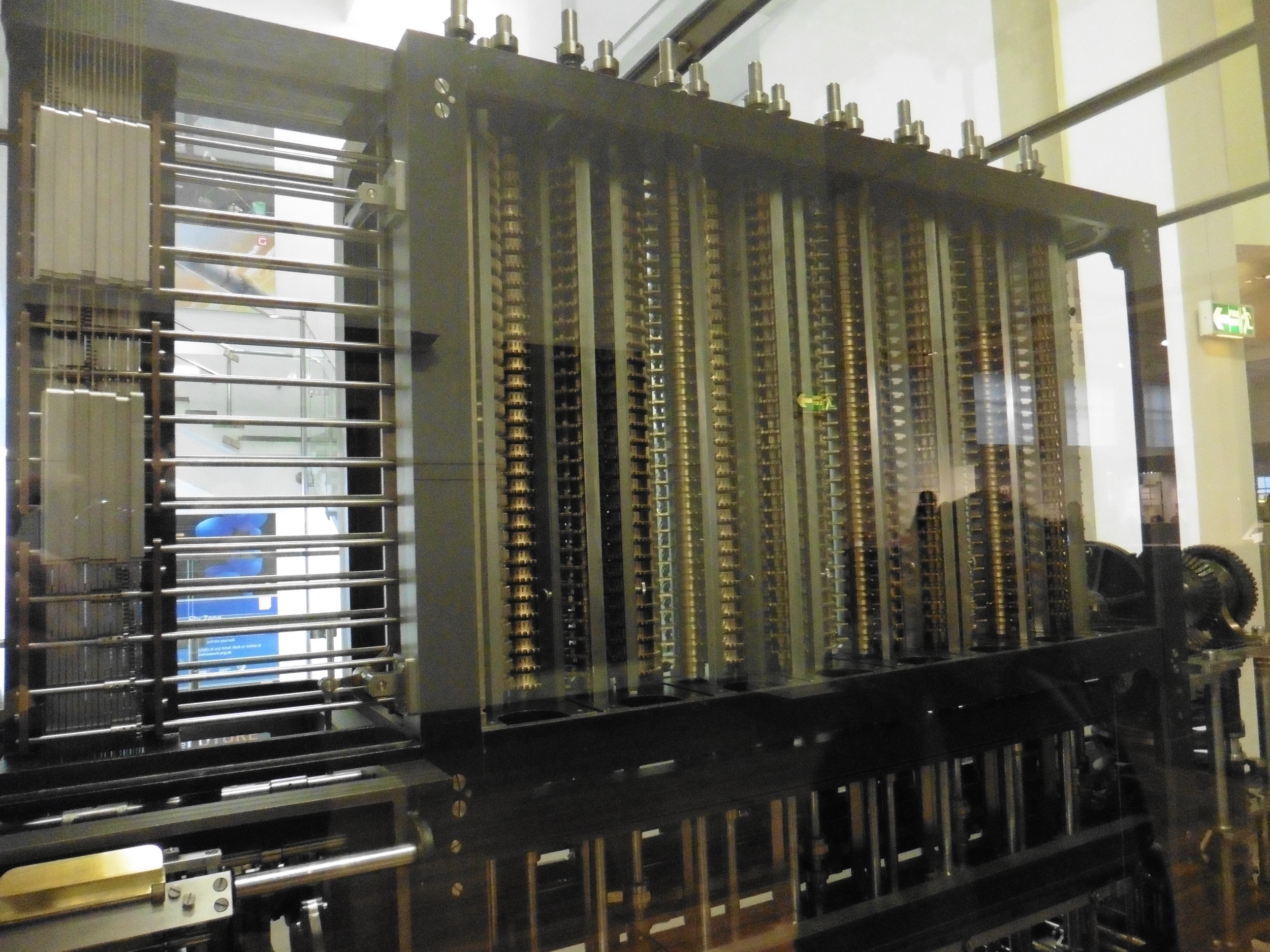

It's not only kids who get moved by this sort of thing. TAround that time I visited the Science Museum in London, and headed straight for the History of Computing section in the Information Gallery. I was fascinated by the Difference Engine that had been constructed by following Babbage's design. All those cogs and wheels and intricacy for doing the kind of calculations that people are able to carry out today with an app on their phone!

But what fascinated me the most was this: in the room dedicated to Ada Lovelace there was on display a lock of her hair. To think that 200 years after she was born, here was I looking at a few strands of her hair. It was almost as if the gap of 200 years didn't exist. I can't explain it, but the feeling was one of wonderment, and of being in the presence of greatness, in the presence of someone who had worked out before anybody else what was possible. Incidentally, check out Thinking Machines: Stories from the history of computing.

I've come to the conclusion that bring the past into the classroom, or the classroom in touch with the past, is a sure-fire way of making the present even more interesting than it already is.

![ENIAC. U.S. Army Photo [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Picture credit for Eniac: This image is a work of a U.S. Army soldier or employee, taken or made as part of that person's official duties. As a work of the …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53b7d42de4b04cfc3188c6eb/1550079821886-TUICJIDYKXZIXMAK0OZX/ENIAC.jpg)